A Little Plastic with Your Meal?

Microplastics are a significant issue, affecting not only the environment but also human health. While we may not have the power to change the overall industry or the level of plastics pollution currently circulating, we can decrease our exposure by changing a few things in the kitchen.

🎧 Prefer to listen? Here’s the narrated version of this post—just press play.

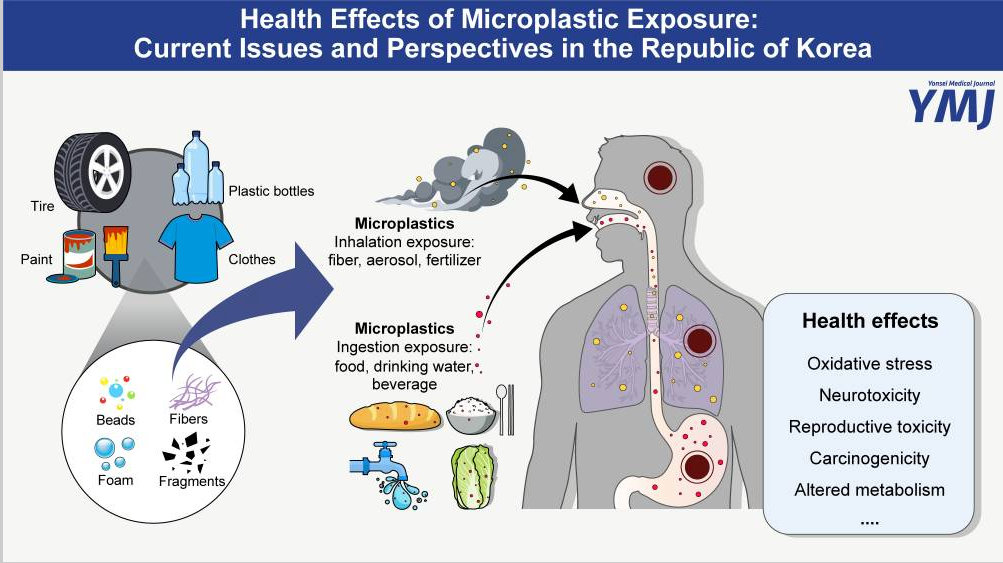

You’ve probably heard about the many problems with plastic. It takes centuries to break down, forms floating garbage patches in the ocean, and kills wildlife like dolphins, seabirds, and sea turtles. But even when plastic breaks down, it doesn’t disappear—it just becomes smaller. Enter one of the newest identified health hazards: microplastics.

Microplastics are now everywhere. They’ve been found in Antarctic ice, in the air we breathe, in our food, and even in human blood, lung tissue, breast milk, placenta, and sperm. According to the Environmental Working Group:

Humans consume microplastics through the food we eat, the water we drink, the air we breathe and the things we touch. An average person absorbs an estimated 39,000 to 52,000 microplastic particles a year with food and drink. The number of inhaled microplastic particles is estimated to be between 35,000 and 69,000 particles in a year.

Microplastics come from various sources, including plastic packaging, synthetic fabrics, carpeting, personal care products, car tires, nonstick cookware, toys, electronics, and plastic kitchen tools, among a zillion others. They're part of the modern world now—but that doesn't mean we have to give up hope.

It’s important to acknowledge that plastic has real value. In healthcare, aviation, technology, and even food safety, plastics have saved lives and made incredible things possible. But not all plastic is necessary. We don’t need cucumbers shrink-wrapped in plastic. We don’t need prewashed greens in a clamshell. We don’t need a new plastic bottle every time we buy soap. If we can start saying no to unnecessary plastic, we can make a real dent in the environmental, social, and health outcomes of our microplastics problem.

Do Microplastics Make Us Unwell?

Research is showing evidence of consequential, adverse effects of micro and nano plastics on human health, affecting the brain, lungs, immune system, digestive system, cardiovascular system, reproductive system, and liver/spleen most significantly. That's practically all the systems we've got!

Our digestive systems may be affected by physical irritation, toxic chemicals in the plastics themselves, and changes in the intestinal microbiome. Microplastics may cause oxidative stress in the airways and can consequently lead to low blood oxygen concentrations. Damage to mitochondrial respiratory cells has been shown, and the plastics also carry other environmental toxins that harm lung cells. These microplastics have also been shown to interfere with the production of various hormones, which can lead to many issues, from developmental disorders to miscarriage, infertility, and congenital malformations.

It's serious stuff. What can we do if it's in the air we breath? Well, we can change what we have the power to change to limit our exposure and minimize our part in the demand for unnecessary plastic goods. Let's focus today on the kitchen.

In the Kitchen

A surprising number of items in our kitchens expose us to microplastics—for example, nonstick cookware. A 2024 study revealed that non-stick cookware releases thousands of microplastics into our diets, even when new and unscratched. An earlier Australian study showed that scratched coatings may lead to the release of 2,300,000 microplastics and nanoplastics. Many people use these pans for ease or to reduce their oil consumption, but there are frypan cooking methods that use no oil that can help folks make the transition to healthy cookware: cast iron, enameled cast iron, glass, and steel. Rather than having a little plastic with your dinner, consider swapping to these cooking pans and reducing your exposure.

Plastic food containers are another big issue, both our "Tupperware" and take-out containers. Not only do these expose us to large numbers of microplastics, but they also have other potentially hazardous additives that can build up in our systems and cause health issues. This is especially true if used in the microwave. You should always transfer items to glass before microwaving. This is an easy fix. Don't buy any more plastic food storage containers. Instead, buy glass, metal, or ceramic. An affordable way—and a way that honors the Re-use R of the three Rs (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle—and we should put 95% of our attention on the first two)—is to wash out jars that once had almond or peanut butter, jelly, date syrup, or other products. It's even pretty cool to have a shelf of mismatched, upcycled containers for your beans, tea, spices, and leftovers. You can also get canning jars inexpensively at thrift stores. Some even have glass lids.

Cutting boards and plastic utensils are other sources of exposure to microplastics in the kitchen. This is easily remedied by getting a wooden cutting board and wooden or metal utensils. The best types of wood are maple, beech, hinoki (Japanese cypress), and walnut. You might think bamboo is a good choice since it's frequently advertised as sustainable, but it's glue-heavy, hard on knives, and can easily split. It takes a bit of care, but wooden cutting boards are beautiful and what many chefs prefer. Wooden or stainless utensils are also great.

Water. There's not much you can do to immediately prevent microplastics from being in your drinking water. But you can filter your water. Not all filters will grab microplastics, but some do. I use Lifestraw, in part, because their filters remove bacteria and parasites, making them suitable for emergency use with water from sources other than a tap, and in part because they donate water purification to communities in need. They also make a glass pitcher, so you're not buying more plastic to get rid of plastic. Burkey is another superb choice. Their filters can also be used on non-tap water sources, as they filter out bacteria and parasites, and their dispensers are stainless, along with the spigots in some models. This is a lifetime pitcher, so if you can afford it, it's a great choice.

The Social Cost of Plastics

The environmental cost of excess plastic is obvious. I can't imagine anyone over the age of 10 not knowing that fact. However, worker safety in industries that directly or indirectly produce plastic, as well as the health of those living near plastic-producing plants, is another substantial concern. A review in Annual Global Health showed that:

Plastic production workers are at increased risk of leukemia, lymphoma, hepatic angiosarcoma, brain cancer, breast cancer, mesothelioma, neurotoxic injury, and decreased fertility. Workers producing plastic textiles die of bladder cancer, lung cancer, mesothelioma, and interstitial lung disease at increased rates. Plastic recycling workers have increased rates of cardiovascular disease, toxic metal poisoning, neuropathy, and lung cancer.

The same report showed that people who live in what are called fenceline communities—those adjacent to production or disposal sites— "experience increased risks of premature birth, low birth weight, asthma, childhood leukemia, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and lung cancer."

When we buy unnecessary plastics, we are, whether we want to or not, contributing to the demand that supports these unsafe conditions. Such conditions often impact those of lower income due to lower housing costs near factories. If we can decrease our demand where we can, we can make an impact.

Revisiting the Three Rs

Today's post suggests replacing plastic items that you already own to decrease your exposure to microplastics during their use. But I usually don't encourage people to consume more, which makes me think again about the three Rs, a public service campaign born in the 1970s. It was an outstanding campaign, meant to be considered in a hierarchy: first, reduce your purchases by reusing what you already have; then, recycle what can't be reused.

However, many industries did not want to weather a reduction in sales, and they helped shape the way that we typically act on the three Rs now: almost exclusively recycling. This has created a sense that buying plastic items is fine; we'll recycle them later. But in truth, only about 9% of plastic waste in the U.S. is recycled. The recycling process itself has environmental costs, such as energy expenditure and toxic byproducts, so it's not exactly a clean solution.

Buying more isn’t the answer most of the time: I stick by that. The most sustainable option is almost always the one you already own, which achieves the first two Rs. But some things are worth replacing, like plastic items in the kitchen.

Use what you have, upgrade what you can, and buy with intention. If you wouldn’t want it ending up in your drinking water or your bloodstream, maybe it’s not something that belongs in your kitchen—or your life.

Final Thoughts

It's not just the kitchen that's the problem with microplastics: it's work, the car, the laundry, the toiletries, the clothing. Oh my, the clothing. And I'll write more about that in the future. Meanwhile, consider switching to bar shampoo, laundry soap sheets, and wood-handled toothbrushes and razors. Also, consider replacing indoor carpeting when affordable, and opt for natural fabric clothes (second-hand if possible), and avoid buying multiple items you only need one of.

We can't change the industrial realities of our world on our own or overnight. But we can minimize our household exposure by changing our behavior, which also decreases, even if only a little, demand for these products.

Deeper Dive

Environmental Working Group (EWG) on microplastics

A great podcast with Matt Simon, author of a book on plastic pollution

Please explore my website and my bookshop.org store.

(This blog is not intended to diagnose or treat disease. I am not a physician. Please consult your physician for any medical advice. Thanks.)

Affiliate note: I have affiliate relationships with Bookshop, Azure, and Amazon. If you click through and make a purchase, I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. I strongly support both Azure and Bookshop for their mission-driven models, and I also include Amazon links, as I know many people find it the most convenient and affordable option. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.