Beans and Lentils

Ancient, Affordable, and Unfairly Maligned

When I first started adding beans back into my diet, I was coming off a strict FODMAP protocol. If you’ve been there, you know: it’s not designed for long-term eating—it’s a reset, not a roadmap. Eventually, I wanted to build a more sustainable, nutrient-dense plate. But after avoiding legumes for so long, the idea of eating a bowl of black beans felt... ambitious.

When I first reintroduced them, it was like a reunion, and as it turns out, my gut microbes were just as happy as I was. After starting small, I now eat beans multiple times every day and have fewer digestive issues than ever.

Beans and lentils—collectively known as pulses—have fed humans for millennia. They’ve anchored cuisines from around the world, and they’ve sustained populations through times of plenty and scarcity alike. But in recent years, these powerhouses have taken some heat—especially from corners of the internet promoting ultra-low-carb, carnivore, or "anti-nutrient" fears. Let’s take a look.

Legumes, Beans, Lentils—What’s the Difference?

Let’s clear up some terminology. The term legume refers to the entire family of pod-producing plants—this includes fresh peas and green beans, peanuts, lentils, and what we generally call "dry beans," like black, pinto, soy, cannellini, adzuki, mung, and kidney.

Within that family:

- Beans are typically larger and rounder, though they come in all colors and sizes.

- Lentils are lens-shaped, smaller, and cook faster (brown, green, red, and beluga).

- Pulse is a catch-all term for dry, edible legume seeds, so beans and lentils are both pulses.

Today, I'm sticking with beans and lentils. If you want to see a long list of bean varieties, check this out, but even this list can’t describe the hundreds (thousands?) of bean varieties known.

Why Beans Belong on Your Plate (or bowl)

Beans are rich in protein, fiber, and complex carbohydrates. They’re filling, blood-sugar-friendly, and deeply connected to longevity. If you look at the diets of long-lived populations (like those in the Blue Zones), beans show up over and over.

Here’s a short list of what you’re getting in a typical cup of cooked beans:

- 15g+ of protein

- 13g+ of fiber

- Iron, magnesium, potassium, and folate

- A low glycemic load

- Almost no saturated fat

That’s a pretty impressive nutritional package for a food that is pocketbook-friendly.

Heart Health, Blood Sugar, and More

Multiple large-scale studies support the role of pulses in reducing chronic disease risk:

- Heart disease: A 2021 meta-analysis found that higher legume intake was associated with a 10% reduced risk of cardiovascular disease.

- Type 2 diabetes: Regular consumption helps moderate post-meal blood sugar spikes thanks to fiber and slowly digestible starch.

- Colon cancer: Pulses contain fermentable fibers and polyphenols shown to support colonocyte health and reduce inflammation in the gut lining.

- Weight regulation: High satiety, low energy density, and beneficial effects on insulin sensitivity make beans ideal for maintaining a healthy weight.

What About FODMAPs?

If you’ve ever been told to avoid beans because they cause bloating, you're not alone. Beans and lentils are high in fermentable carbohydrates—specifically galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS)—which are part of the FODMAP (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols) family. These short-chain fibers resist digestion in the small intestine and are fermented by gut bacteria in the colon. For most people, that fermentation is beneficial. For some, especially those with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), it can cause symptoms like gas, bloating, and discomfort, and a low-FODMAP diet can help with symptoms.

However, maintaining the maximum moratorium on higher-FODMAP foods is not ideal as a long-term lifestyle, as avoiding fermentable fibers deprives your large intestine’s resident bacteria of their preferred fuel. This results in reduced production of short-chain fatty acids, such as butyrate, which are essential for maintaining colon health, regulating inflammation, and achieving metabolic balance.

I made the mistake of staying on a low-FODMAP diet for years. Since adding back complex fermentable carbs, I’ve been more regular, had fewer instances of abdominal pain and bloating, and feel better in general. Most people don’t have to give up on pulses entirely. It just requires some strategy.

How to Make Beans More Digestible:

- Start small. Portion size matters—try ¼ cup of cooked beans at first and increase gradually. Many people report that initial issues with adding beans diminish over time.

- Rinse canned beans well. This removes excess oligosaccharides.

- Discard soaking liquid. Soak dry beans for 8+ hours, then drain, rinse, and cook in fresh water.

- Cook with kombu or bay leaf. Both help break down gas-producing compounds.

- Track what works. You might tolerate some pulses better than others—mung beans and lentils often cause fewer issues, while pinto or chickpeas might be trickier.

What About Lectins?

You’ve probably heard some internet guru shout about the dangers of lectins. Beans, along with other plant foods like tomatoes and whole grains, are often flagged as “toxic” because they contain these naturally occurring proteins. But here's the reality: lectins are neutralized by proper cooking. When beans are soaked and thoroughly boiled, as they are in every traditional cuisine that uses them, the potentially harmful lectins are destroyed. Furthermore, the evidence that beans are toxic rests almost entirely on the consumption of raw kidney beans. I doubt you’ve got raw kidney beans on your menu this week.

The news gets even better: some lectins may actually offer health benefits, including supporting the immune system and possibly even reducing cancer risk. The science on this is still developing, but one thing’s clear: avoiding all lectins means avoiding a massive swath of the healthiest foods on the planet.

As Dr. Michael Greger has pointed out (and supported with peer-reviewed data), legume consumption is one of the strongest dietary predictors of longevity worldwide. In his summary of the Blue Zones and global aging studies, just one daily serving of beans was associated with a reduced risk of death by all causes. Not a bad trade for something you can make in a single pot for pennies on the dollar.

Importantly, slow cooking kidney beans is not advisable unless you boil them for at least ten minutes first. (If unsoaked, the necessary boiling time for kidney beans is increased.) I don’t slow-cook any beans, to be on the safe side. If you love kidney beans, one way to be sure you’re avoiding residual lectins is to buy canned.

Cultural and Sacred Ground

Beans are more than nutrition. Cultures around the world celebrate beans and use them as a symbol for potential, rebirth, and good luck. For example:

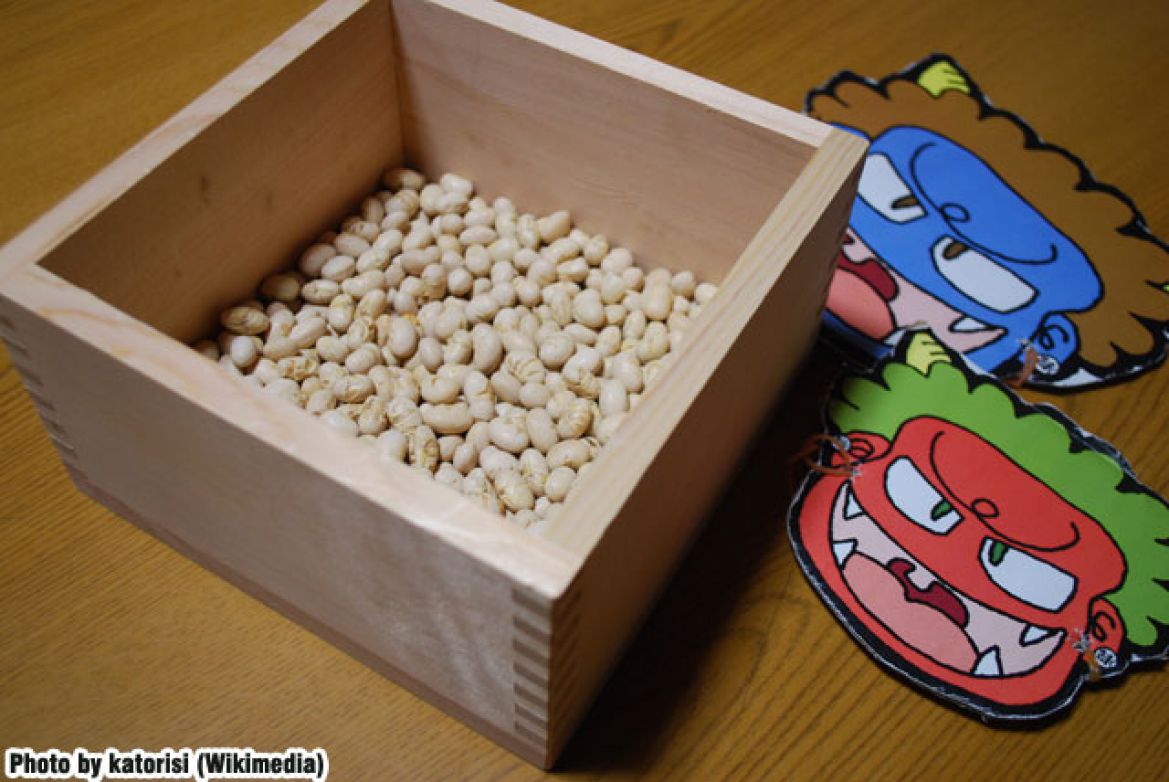

- Setsubun, part of the spring festival celebrated in Japan, involves throwing soybeans on the first day of the lunar spring to ward off evil spirits and bad luck. Some folks do it at their homes, and others in large ceremonies at temples.

- The Three Sisters—corn, beans, and squash—formed the sacred agricultural triad of many Indigenous peoples in the Americas. These sisters are essential characters in many Indigenous stories.

- In ancient Greece and Rome, broad beans were used in ceremonies for the dead, symbolizing rebirth and spiritual connection.

A Sustainability Standout

Pulses are among the most environmentally sustainable proteins on the planet.

- They fix nitrogen in the soil, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers, enabling effective crop rotation systems, and improving soil health.

- They require less water and emit significantly fewer greenhouse gases than animal-based proteins. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), pulses produce 1/10th the emissions of beef per kilogram of protein.

In short, beans are excellent for your body and the planet. They are also grown in the United States, though imported varieties are also widely available, so they can have a small carbon footprint from field to store shelves.

Practical Tips: How to Buy, Store, and Cook

Buying

- Dry beans are more affordable and long-lasting, especially in bulk bins or ethnic groceries. I often buy from Edison Grainery because they take special care to avoid gluten and other potential contaminants. Rancho Gordo is a source of heirloom beans, and Azure Standard has inexpensive organic beans in bulk.

- Canned beans are convenient; rinse well to reduce sodium and oligosaccharides. Eden Foods makes its beans with kombu, which helps mitigate gas and bloating.

Storage

- Store dry pulses in airtight containers away from light and humidity.

- Cooked beans will stay good in the refer for a few days, and in the freezer in their broth for longer.

- Dried beans can last a very long time; however, their freshness does suffer. Experts suggest eating dried beans within one year of harvest for the best taste and texture.

Cooking

- Soak beans 6–8 hours (or overnight), drain, and cook in fresh water until tender (time depends on the type and method). [soak or not?]

- Always boil beans for about 10 minutes if not using a pressure cooker.

- Add kombu seaweed or a bay leaf to aid digestibility.

- For lentils, just rinse and simmer. Time required varies.

Pressure cookers like InstantPot can dramatically reduce cook time. I soak my beans overnight, then use my InstantPot to cook them. Sometimes I include only kombu, bay leaf, and herbs; other times I cut up vegetables to include.

Here is a list of beans, along with their suggested soak and cook times.

Final Thoughts

In a culture that praises protein but tends to forget about plant sources, beans and lentils are quiet warriors. They nourish, replenish, and protect, at a fraction of the cost, and with centuries of wisdom behind them. They belong in our kitchens not only for their nutrition and sustainability, but for their cultural weight.

Want to learn more?

New York Times Cooking: How to Cook Beans

Instant Pot bean cooking guide

Stovetop bean cooking guide

Great book on beans

Check out my full website.

(This blog is not intended to diagnose or treat disease. I am not a physician. Please consult your physician for any medical advice. Thanks.)