Your Gut Has a Clock, Too

Why Routines Feed Your Microbiome

The other morning, I woke up at 4 a.m. for some reason. Let’s say that’s not my usual. I lay awake for a while, thinking I might fall back asleep, but eventually got up, made tea, and even went for a walk before the sun heated up. It was nice to see the sun low in the sky just over the hills. Since I had a significant sleep deficit that night, I went to bed around 9:30 and woke up at 6:00 the next morning, a very respectable time to rise and start the day.

Since then, I’ve been naturally waking up at 6:00 a.m. That’s a win for morning walks (important in the hot season) and added productive time (I wake up raring to go and tend to slow down a bit by mid-afternoon). However, what I wanted to discuss today is another consequence of my adjusted sleep schedule: I've started feeling truly hungry again.

That might not sound like a big deal, but as someone who often eats out of necessity, habit, or a desire for a taste rather than deep physical hunger, this was a huge difference. I was hungry in the way toddlers are hungry—insistent, three or four times a day, like clockwork. That’s when it hit me: something had found its stride. Not just my sleep, but something more profound: my body’s whole timing system.

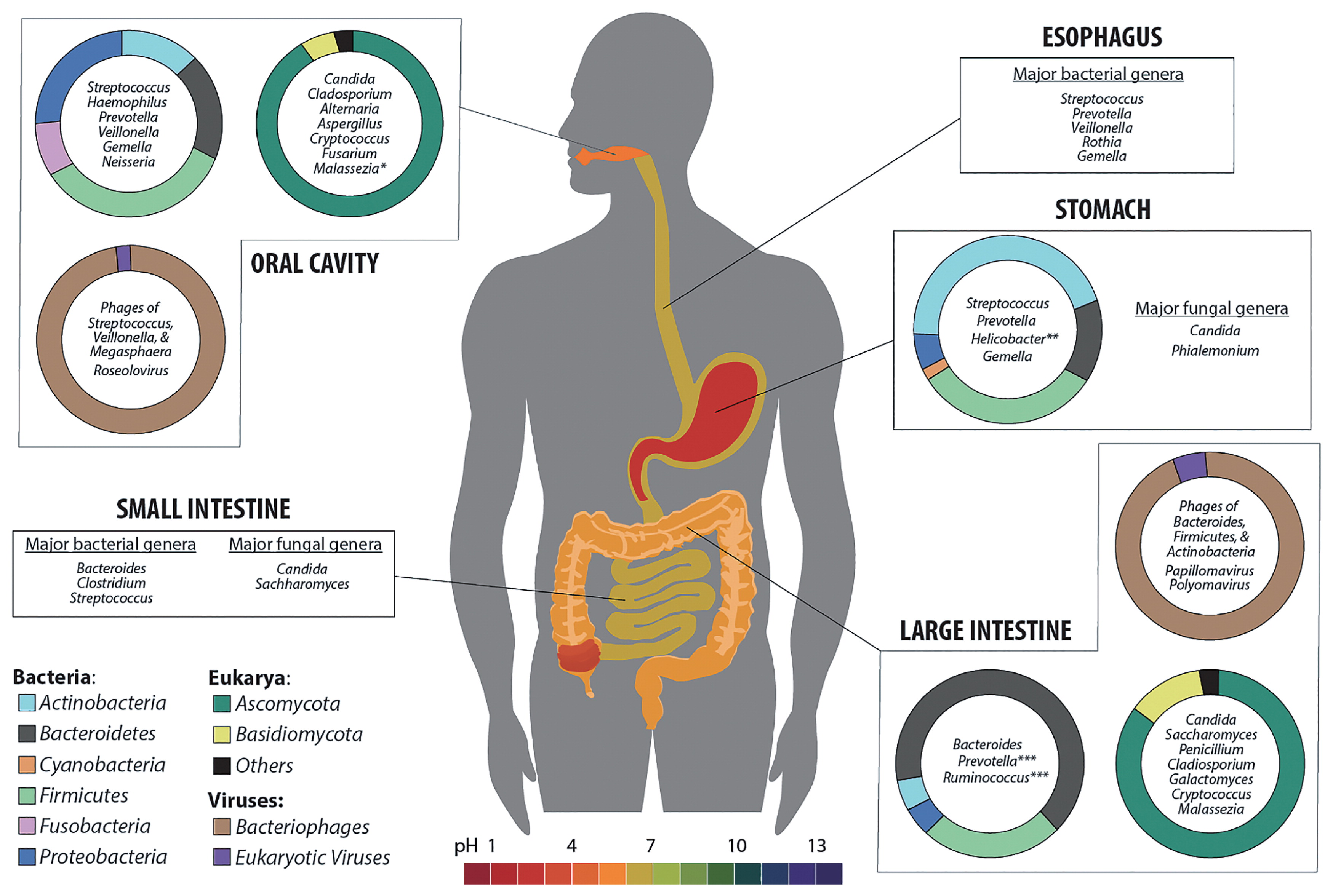

The title of this post gives it away: Your gut has a clock. More precisely, trillions of gut microbes—bacteria, fungi, viruses, and archaea, each with its rhythm—work best when our behavior supports a regular internal schedule. Disrupt that, and they don’t just get cranky, they get sloppy. This results in increased inflammation, less efficient digestion, and weakened protection against pathogens.

The Gut Clock, Explained Simply

The circadian rhythm isn’t just about sleep. It’s a 24-hour system hardwired into nearly every cell in your body, including those in your gut lining. The microbes that live in our body have a matching rhythm, as we evolved to work synergistically.

Research backs this up. Gut bugs change in number and function throughout the day, depending on light exposure, food intake, activity, and hormones like melatonin and cortisol.

Nighttime is when intestinal repair and microbial shifts occur—if we’re asleep. If we stay up late, snack at midnight, or skip consistent meal times, it scrambles that schedule.

Digestion peaks from morning to midday. That’s when the gut is primed to receive food, digest it efficiently, and absorb nutrients.

“Figure 1. Model of cooperative host-microbial diurnality. Light entrains the master clock of the host, whose rhythmic activity determines the time of food intake. Feeding times are controlling diurnal activity of the microbiome, which in turn is necessary for metabolic homeostasis of the host.” (Image and image description from Thaiss, C. A., Zeevi, D., Levy, M., Segal, E., & Elinav, E. (2015). A day in the life of the meta-organism: diurnal rhythms of the intestinal microbiome and its host. Gut Microbes, 6(2), 137–142.

Our modern world, with its electric lights, night shifts, and alarm clocks, makes it easy for us to disrupt our natural circadian rhythms, which is associated with several chronic diseases, like diabetes, insulin resistance, obesity, and cancer. Individuals who work nights or who keep irregular hours are at a higher risk for these conditions, and research suggests that those with these conditions often have a disrupted microbiome. Our guts need downtime to perform tissue repair and other beneficial activities. If we eat too late or fail to wake and go to bed according to the human, hard-wired diurnal schedule (associated with light exposure), we are not doing ourselves any favors.

Additionally, the relationship between the gut and sleep appears to be bidirectional. Imbalance or dysfunction in the microbiota impairs sleep quality. Some beneficial gut bacteria produce serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), both of which are known to aid in sleep. Sleep deprivation reduces beneficial bacteria, making it harder to sleep, and creating a loop.

Why This Matters for Digestion

When your gut microbiome is on a consistent rhythm, your digestion runs more smoothly—literally. Specific gut bacteria populations rise and fall in a predictable 24-hour cycle, helping you break down food, absorb nutrients, and facilitate the movement of waste through the intestines. Eating at irregular times or skipping meals entirely can disrupt this rhythm, reducing digestion efficiency and potentially leading to bloating, irregularity, or discomfort.

Studies in both mice and humans have shown that timed eating patterns, such as eating during daylight hours, enhance the activity of beneficial microbes and increase the production of short-chain fatty acids, including butyrate (an essential gift given by our gut bugs). These byproducts help fuel the cells lining your colon, maintain gut barrier integrity, and reduce inflammation in the GI tract.

Disrupting this rhythm through shift work, jet lag, or late-night eating can lead to microbial imbalance, increasing the risk of constipation, diarrhea, or even longer-term gut conditions like IBS. Getting your gut bugs on a regular schedule with you makes digestion more predictable and comfortable.

It Goes Beyond the GI Tract

Your gut microbiome doesn’t just handle digestion—it’s a command center influencing nearly every system in the body. Research has shown that gut microbes help modulate the immune system, produce neurotransmitters such as serotonin and GABA, and play a crucial role in regulating the body’s inflammatory response. Approximately 70% of the immune system is located in the gut, and microbial metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids, communicate directly with immune cells.

There’s also a growing body of evidence linking an imbalanced gut microbiome with mood disorders, such as depression and anxiety, through what's known as the gut-brain axis. It’s also recently been tied to sleep apnea. The biome is a massive player in the whole system. You’ve probably heard that there are more bacteria cells in your body than human cells. While they are not all in the digestive tract, it’s nonetheless easy to see how influential the human microbiome is.

By syncing your lifestyle with natural circadian cues, like eating at regular times and sleeping in rhythm, you support the microbial processes that, in turn, support you. This is a true symbiosis: give your microbes consistency and nourishment, and they’ll help regulate not only your digestion, but your mental clarity, sleep quality, immune resilience, and hormonal balance.

What This Means for You

You’re not just feeding yourself. You’re feeding your microbes—and they’re picky eaters, both the what and the when (more on the what in a future post).

Regular meal times help beneficial bacteria thrive.

When we eat erratically or too late, we disrupt natural microbial rhythms that govern metabolism and immunity. Intermittent fasting (especially early time-restricted eating, where you eat earlier in the day and fast at night) has shown positive effects on the gut microbiome in both animal and human studies.

You’ve probably heard the old saying: “Eat breakfast like a king, lunch like a prince, and dinner like a pauper.”

I like to reimagine it like this: “Eat breakfast like a sovereign, lunch like a scholar, and dinner like a sage.” It nods to agency, learning, and calm—a more mindful way to fuel your day.

Early rising and morning light help set your gut clock.

Your brain’s master clock (the suprachiasmatic nucleus) syncs with sunlight, but that signal travels downstream to the gut. Morning light exposure helps regulate the rhythms of cortisol, melatonin, and digestive hormones, such as ghrelin and leptin, which all influence microbial behavior.

Sleep timing matters.

Going to bed and waking up at consistent times helps your gut bugs keep their schedule. The gut lining repairs itself during deep sleep; disruptions here may increase intestinal permeability (leaky gut), which has been linked to inflammatory conditions and mood disorders.

So What Can You Do?

If your routines are all over the place, don’t feel guilty. Instead, choose a change to try and build from there.

- Wake up and eat around the same time every day, even on weekends. Your gut likes reliability.

- Get morning sun exposure, even for just 10 minutes. Not only does it give you a splash of vitamin D and get you started on your day, but it may also help you fall asleep more easily when you go to bed at night.

- Eat the majority of your calories earlier in the day. Digestion is strongest then. If you don’t love a big breakfast, focus on a substantial lunch.

- Avoid late-night eating. Your gut bacteria want to rest, too. Your ability to digest things later at night is compromised, so you won’t get the same nutrition and may set yourself up for digestive distress, as well.

- Prioritize sleep hygiene. A warm foot bath or hot shower before bed, dim lights in the evening, and cool room temperatures can all help. (More on this in my upcoming sleep post.)

- Eat lots of fiber and prebiotics. More on this in a future post, but including beans and lentils is a huge win here.

Takeaway

It’s been a week now that I’ve been getting up early. I even go on a walk “with” my mom. We talk on the phone while we each walk in our neighborhoods. This would be impossible if we had to start any later than 6:30 a.m.

Most importantly to me, I’m able to eat three or four meals a day, be hungry for each of them, and know that I’m giving my microbiome food when it wants it and rest when it wants it. The stronger my digestion, the better my overall health, the better my sleep, the better my digestion. It’s a real winning track.

Resources

Microbiome: We Are What They Eat, a video by Dr. Greger.

Cleveland Clinic on microbiome health.

Nutrients article on Chrononutrition.

Check out my full website.

Explore my bookshop.org store for books on the biome and related subjects.

(This blog is not intended to diagnose or treat disease. I am not a physician. Please consult your physician for any medical advice. Thanks.)